Maurice Gatsonides; race driver (1953 Nurburgring), rally driver (outright winner, 1953 Monte Carlo Rally), sports car manufacturer (Gatso, Gatford), and successful inventor, (electronic speed traps) was a tour d’force, yet little is known about this fascinating man. In a stroke of luck, in conversations with our correspondent Gijsbert-Paul Berk, it was revealed to the Editor that Berk once called Gatsonides his boss. Do tell more, we asked. Thusly, here is Berk’s personal memoires of the multi-talented Dutch carmaker and a photo history of the man and the cars.

By Gijsbert-Paul Berk

Photos courtesy Gatsonides family and Gatsometer BV

At the Dutch Institute for Automobile Management where I studied in 1948, it was a tradition that each autumn a group of students had to organize a TSD rally for students, parents and special guests. One of these guests was Mr. Maurice Gatsonides, a well-known Dutch rally driver and the builder of the Gatso sports car.

On the day of the rally I drove with my friend Paul, who had managed to borrow his father’s Lancia Aprilia, for a last check of the first part of the route and to set up the last checkpoint of the morning. We had hardly installed our camping table with the chronograph clock and a stamp pad, when we heard the unmistakable rumble of a V8 engine. A few seconds later a streamlined and low, light grey car came in sight and stopped in a cloud of dust. With its central headlight it resembled a Cyclops. “Hey chaps”, shouted the driver. “You know that you are at half a kilometer ahead of the place where your checkpoint should be?”

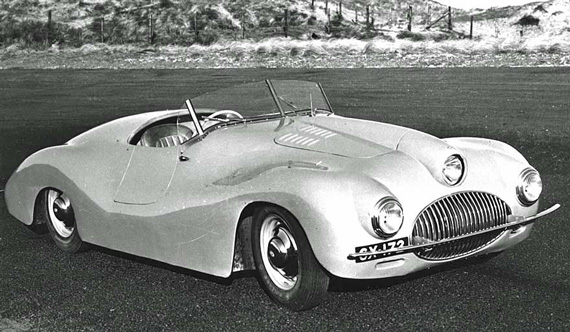

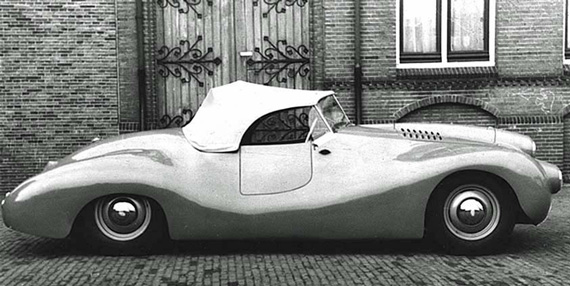

The lines of the Gatso were as unmistakable as its Ford V8 rumble. This is Gasto number 3, bought by Swiss bobsled champion Felix Endrich.

Paul and I, who had covered the whole route several times, knew that our checkpoint was in exactly the correct spot. As I later would learn, this was the way Gatsonides often reacted. He tried to bluff, because he had driven too fast and arrived minutes early, which would cost him penalty points. However, I went to his car and, using his own road book, politely convinced him that he had miscalculated his average speed.

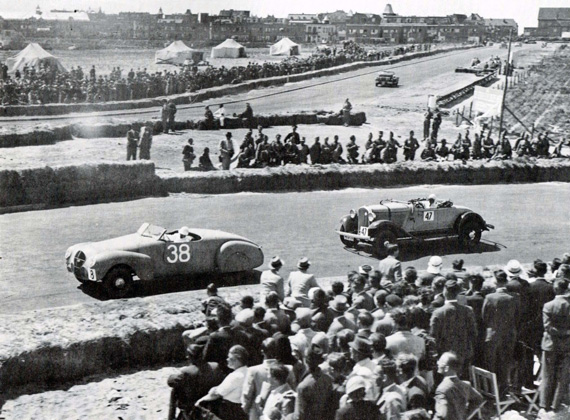

Gastonides was racing before the war. With Ford based Mercury engined special, nicknamed ‘Kwick’, (number 38) Gatsonides participated in both races and rallies. Here we see him in action during the 1939 sports car races around the streets and seaside boulevard at Zandvoort.

During the lunch break we met again and I asked a lot of questions about his Gatso sports car. He enthusiastically showed me everything. As part of our study, we were required to do a few months of practical work in the motoring trade, so I also asked him if he ever employed apprentices. He told me to contact him when this became opportune.

The ‘Kwik’ resting after the 1939 Liege-Rome-Liege Rally next to one of the streamlined Auto Union sports-racing car. Later Gatsonides would gladly admit that the shape of this car inspired him when in 1945 he designed his first Gatford.

Twenty month later we met again. Gastonides agreed that I could work from September to the end of the year as an apprentice in his Rootes dealership in Heemstede, a wealthy suburb of the Dutch town of Haarlem near Amsterdam. As he was going to participate in the next Monte Carlo Rally with a large Humber Super Snipe – loaned to him by the factory – during most of that time he would be in the south of France to reconnoiter the various special stages. During his absence I had to report to Nico Stuifbergen, his chief mechanic and the foreman of his workshop.

Presenting his Gatso Aero Coupé to HRH Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands at the 1948 Amsterdam Motor Show. The Prince (in glasses) never bought a Gatso but became a lifelong admirer and friend of the versatile Gatsonides.

I must admit that I was slightly disappointed with the tasks attributed to me. Early in the morning I had to drive the cars that were parked overnight in the workshop to the forecourt. Occasionally I had to deliver these cars to their owner’s houses. (In those days it was not unusual for car owners who had no garage to rent a space in a professional garage to store them when not in use.) Then I had to help in the greasing pit to change oil and with a Tecalamit pump, lubricate the multitude of greasing nipples most British cars had in those days. Sometimes I had to take an old Hillman van to fetch spare parts in neighboring Haarlem.

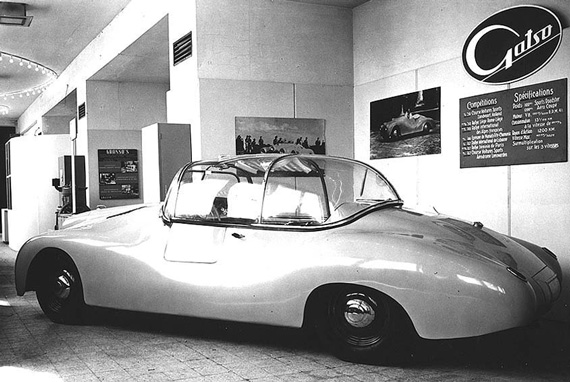

Three-quarter-rear view of the Gatso Aero Coupé on the exhibition stand at the Swiss Motor Show in Geneva. The aircraft-inspired Plexiglas canopy could slide horizontally backward to allow entry into the cockpit. But on sunny days the interior became unbearable hot, and sliding the canopy slightly back produced drafts and wind noise at speeds above 80 km/h.

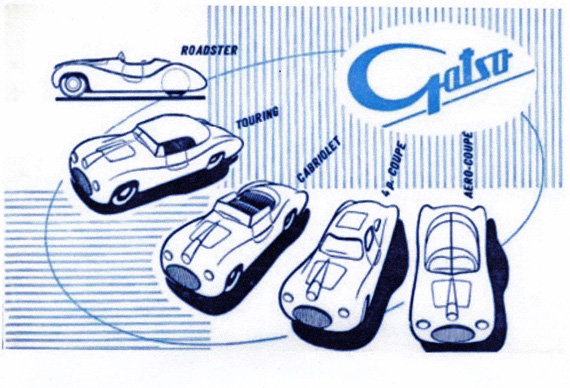

I wished for tasks with more responsibility. I had approached Gatsonides in the hope to become involved in building the Gatso car, because I was interested to learn more about car design and development. However, I soon discovered that there was no regular series production. Each car was different and built according the wishes of the customer, and most of the work was outsourced to coach building companies in Haarlem and The Hague.

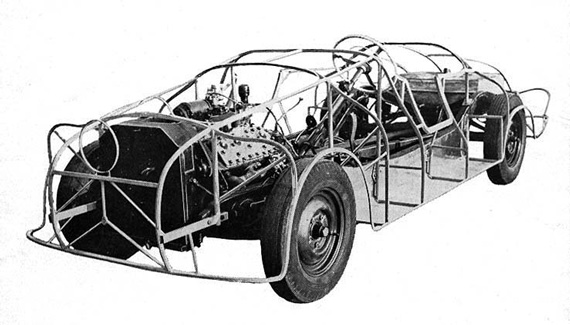

The original Gatford/Gatso chassis was based on that of an American Ford. Later Gatso cars were built on the shorter French Matford chassis. This photo shows the steel frame of the body structure and the flathead V8 power plant.

I also sensed that Gatsonides had lost interest in his sports car venture. He was disappointed because the Dutch subsidiary of Ford at Hembrug, near Amsterdam had always sponsored motor sport activities. But the new management refused to provide him with chassis, components and V8 engines at the normal dealer discount. This of course had a negative effect on the cost price and thus the commercial potential of his cars. So, notwithstanding many enthusiastic articles in the international motoring press, sales never took off. This explains why only a few Gatsos were built. Including the last Gatso called Platje (Flatty), based on a modified chassis of a six cylinder Fiat 1500 with independent Dubonnet suspension at the front, you can count the total production on the fingers of your hands.

Therefore, to be honest, I was hardly surprised when one evening in December, Gatsonides phoned and told me that he had sold his enterprise in Heemstede. He was sorry, but my apprenticeship was therefore terminated. The next January I went to Paris to try my luck with the coachbuilders there.

Holland is a small country, and our paths would cross again.

Part 2 August 29th

How wonderful to have had an apprenticeship with this man at such an interesting time. I look forward to reading Part 2.